Listening to Artistic Music, Score Study and Composition Planning

Education • Updated June 20th, 2022

I‘ve always been told it’s important to study scores as a musician and especially as a composer, but it’s taken me years to learn how to maximize my time spent with my head buried in notated music. For that matter, I know it’s extremely important to listen to music, but when I first began my graduate studies in contemporary classical composition and became exposed to music like Jennifer Higdon’s blue cathedral, commissioned and premiered by the Curtis Institute of Music:

cred. Jennifer Higdon blue cathedral

I seriously didn’t know where to start! I wanted to obtain a deep understanding of what the Ms. Higdon’s masterpiece is communicating, but I didn’t know how to approach the music. Through much individual study, as well teaching Music Appreciation classes to non-majors, I have found that instrumental artistic music may not seem accessible at first, but a methodical approach to understanding its elements enables us to listen actively and describe accurately what is taking place in the music. For my current Music Appreciation classes, I introduce this set of parameters:

And then I introduce different vocabulary words associated with each term that we can use to describe what we are hearing. For instance, we can define melody as the primary tune of a song, but to describe its motion we use words like ascending, descending, conjunct (stepwise) and disjunct (containing leaps). Another term – texture – sometimes is used to describe how dense a passage of music is. (it is also inaccurately used to refer to instrumentation commonly. Keep in mind, texture is not synonymous with orchestration!) Texture can also refer to monophony, homophony and polyphony. Check out this fun exercise to hear the difference between these three terms in George Frideric Handel’s ever-popular, the Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah. For monophony, which is everyone singing or playing the same notes at the same time, listen to the words “Kings of Kings” and “Lord of Lords” beginning at the two minute mark. For homophony, look at the very first entrance of the chorus at :13. And for polyphony, begin listening at 2:39 to the multiple entrances of similar parts overlapping one another.

cred. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir Hallelujah Chorus

After an introduction to each of the parameters and much practice on the vocabulary words, the rest of the semester is then spent on exploring these elements chronologically through history with different musical examples, from the Middle Ages all the way through today (yes, even dubstep included!). By the end, I’m always so proud of how well many students can listen to something and then describe its sequence of events using descriptive terminology. I’m also always thrilled at how many students grow in their interest for different types of music that they simply might not have been exposed to previously. When first agreeing to teach MUSI 1306, I did not expect how much better of a composer my experience as a teacher would make me. As a result of learning to listen and speak about music well, my score study time is more productive and I am becoming a more confident, intentional and skilled decision-maker as a composer. For the scope of this article, I’ll show you one approach to listening to music, and then I’ll dig deeper into the practical habits of my score study phase, and how this time aids me in creating a compositional plan during the sketching phase. (For an overview of my entire creative and entrepreneurial process, check out this article here)

Listening to Music

Let’s go back to first video I included at the beginning of the article – blue cathedral by Jennifer Higdon, one of the most performed orchestral compositions by a living composer today. One approach in listening to this work is to take a look at Ms. Higdon’s program notes, (which are easily found by doing an internet search for “blue cathedral program notes”) and identifying key words that create an expectation in us as listeners. Here are a few excerpts for our discussion, with my key words highlighted in bold: Blue…like the sky. Where all possibilities soar. Cathedrals…a place of thought, growth, spiritual expression…serving as a symbolic doorway in to and out of this world. As I was writing this piece, I found myself imagining a journey through a glass cathedral in the sky. Because the walls would be transparent, I saw the image of clouds and blueness permeating from the outside of this church. In my mind’s eye the listener would enter from the back of the sanctuary, floating along the corridor amongst giant crystal pillars, moving in a contemplative stance. Using the parameters list from above, think of different ways a person could go about communicating the key words to an audience. “Sky”, “soar”, “clouds” and “floating” all tell us that the work will aim to give a feeling of not being grounded. How might this be accomplished? Here’s a few ideas:

Ms. Higdon’s program notes also have very practical information for guided listening. Take a look at another excerpt from the same program notes: I wanted to create the sensation of contemplation and quiet peace at the beginning, moving towards the feeling of celebration and ecstatic expansion of the soul, all the while singing along with that heavenly music. It is clear from this statement that we can expect the energy level of blue cathedral to be very low at first, and growing continuously. Here are some thoughts on how Ms. Higdon might accomplish the bold words, again using the parameters outline:

Finally, take a look at this excerpt from Ms. Higdon’s notes: I began writing this piece at a unique juncture in my life and found myself pondering the question of what makes a life. The recent loss of my younger brother, Andrew Blue, made me reflect on the amazing journeys that we all make in our lives, crossing paths with so many individuals singularly and collectively, learning and growing each step of the way…In tribute to my brother, I feature solos for the clarinet (the instrument he played) and the flute (the instrument I play). Because I am the older sibling, it is the flute that appears first in this dialog. At the end of the work, the two instruments continue their dialogue, but it is the flute that drops out and the clarinet that continues on in the upward progressing journey. This is a story that commemorates living and passing through places of knowledge and of sharing and of that song called life. Especially in combination with the previous excerpt, which told us that the work would begin quiet and travel to a place of celebration, this gives a huge insight into expectation for the form of the work, which refers to how a piece is structured. Often times, stories in literature, film, music, etc. introduce information, transition away from the information, and then return to it creating an ABA structure, which is known as ternary. Since Ms. Higdon states she will begin and end with the flute and clarinet soloists in respective order, a reasonable expectation is that we may encounter a ternary form with the work. With either this evaluation or your own evaluation in place, you are now able to listen and can make observations about how the work met and deviated from your expectations. You can also derive an opinion about how successful the performance and work itself is in what it is attempting to accomplish, and be able to support your stance with concrete examples!

Score Study

To dig deeper, I take my observations about the work, and investigate how the composer wrote the music in detail by obtaining and studying the score. For instance, my classes often report that in blue cathedral they can perceive the writer struggling through the stages of grief to a place of acceptance. Therefore, an objective of studying blue cathedral for me is to investigate how the oscillating feeling of nostalgia vs. the present is accomplished. At first glance, as I listen through, there are many abrupt phrase endings, and sudden changes in key center. In score study, I would compare and contrast each of the phrase lengths, and what the key changes are exactly. (On a personal note, I know from experience that after losing someone our thoughts often center around our memories of our loved one, but are confronted with the increasingly realization that they are gone. A great composer in my opinion is one who can communicate deep, relatable truth and experience to an attentive listener, regardless of the listener’s background. blue cathedral is the most common work my students actively search for live performances of, which is the best way I know to compliment Ms. Higdon and her incredibly moving work.) My findings as a result of score study would be especially helpful if I was writing a work that addressed the issue of grief, regardless of whether or not the performing ensemble is an orchestra or not. As a reference, here is a list of questions I recommend to composers in gathering scores to find inspiration and techniques to start a work of any kind:

Once a composer has determined their practical and communication goals for the work, has listened and located music that accomplishes similar goals, and has located the scores and recordings, the next step is to dig in to the scores. And for me, this is regardless of the difficulty level of the work! In my last article exploring young band music on the Texas PML, I reported my findings in the areas of Key, Theme, Length, Tempo, Meter, Difficulty Level, Range, Melody and Harmony after studying fourteen of the most popular works on the list. Although all the areas are extremely important to me, it was especially helpful to find the right length for my new band pieces this Spring, and so I determined the range, median and mode after comparing and contrasting these works:

The theme of the works was also really important to me:

And besides learning this information for myself, I have also started a PowerPoint presentation should I decide to do a clinic presentation on the subject of young band music down the road. And, I was able to use the pretty slides for this blog!

Additionally, the benefits of copying and transcribing scores can not be overstated. Even the great J.S. Bach was rumored to spend many hours copying Handel’s music by hand. Personally I find that writing music into my notation program helps me battle the ever-difficult struggle with hearing how something sounds played back from the computer vs. how something will actually sound in live performance. If I start with something that is already recorded well, and then notate it, I can see what the composer heard on playback before hearing the musicians play it.

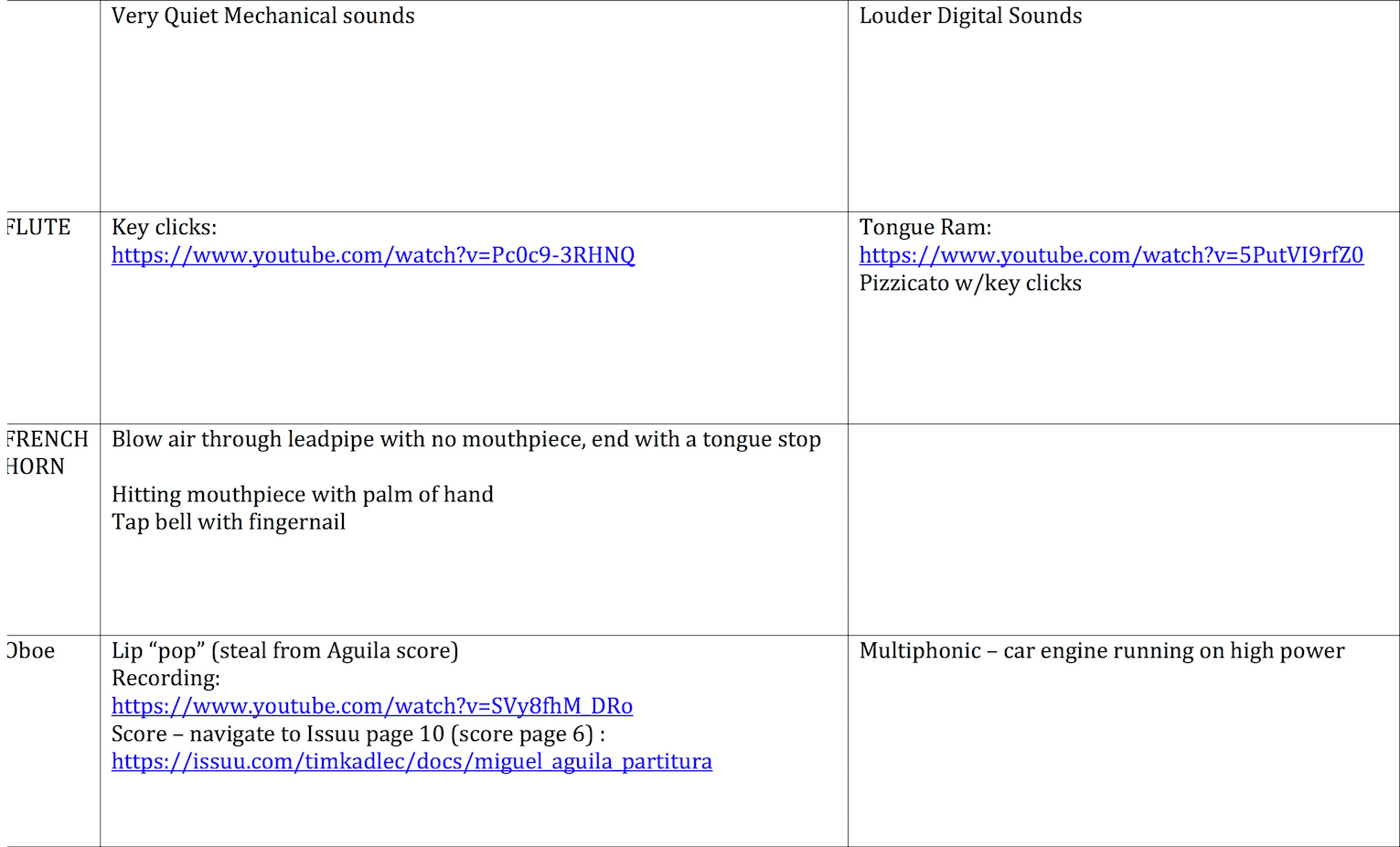

Yet another habit to consider developing is to create resources for yourself from your score study time. Last year, I wrote a piece with the intention of communicating sounds of a car factory and sounds from the digital age, scored for Woodwind Quintet. Reaching out to my woodwind performer friends was incredibly beneficial, as I asked them if they had any ideas as to different sounds their instruments could make. In combination with studying scores and recalling past performances, I created this chart that I’ll have as a reference for the future:

The main point to come back to is to remember to study strategically, especially if you are studying with the intent to write a new work. I feel studying scores is often like putting money in the bank, and writing is spending that money. Go into your study with specific goals in specific parameter areas (form, harmony, etc.) and if possible make resources for yourself and others of your findings.

Composition Planning: Structure and the Golden Mean

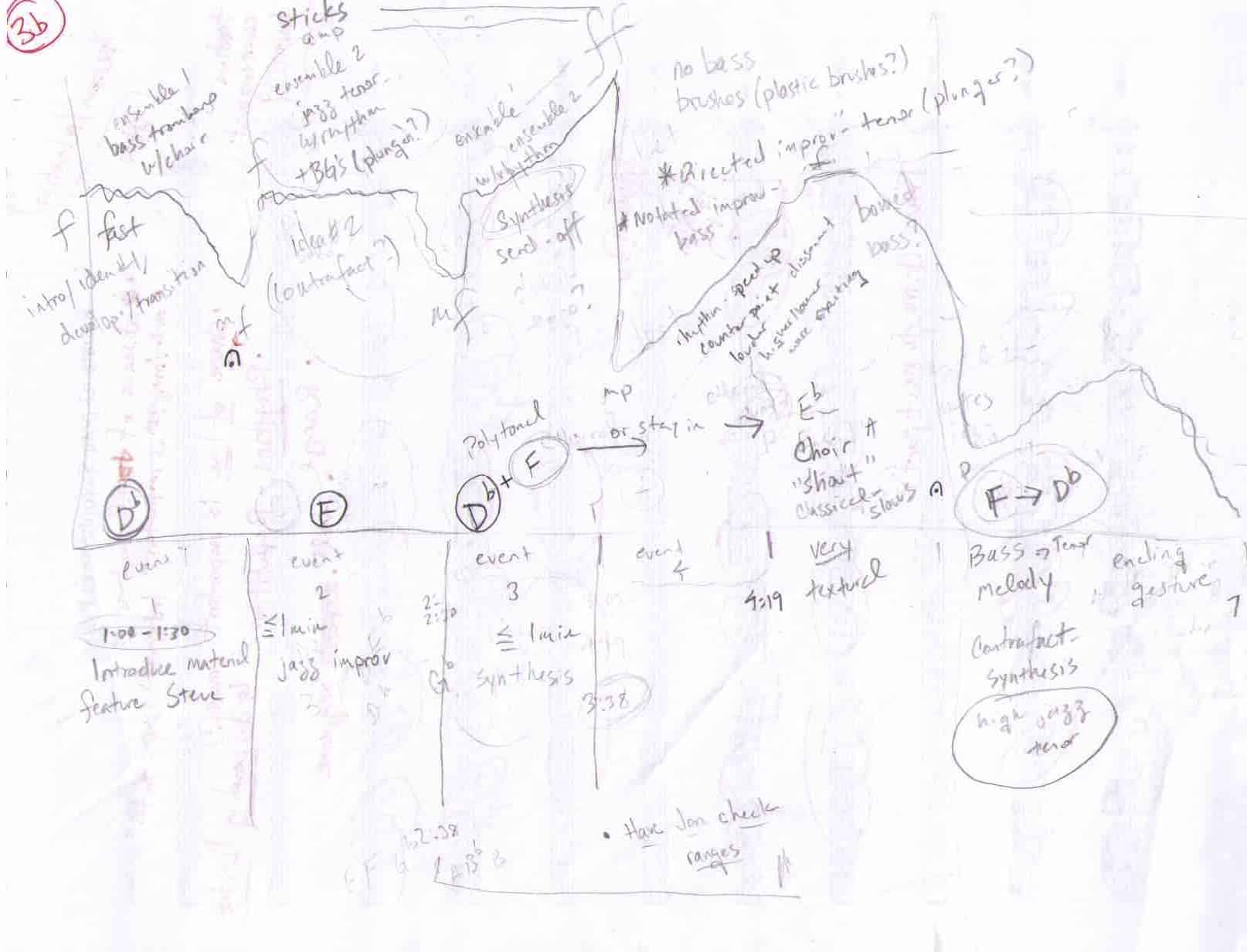

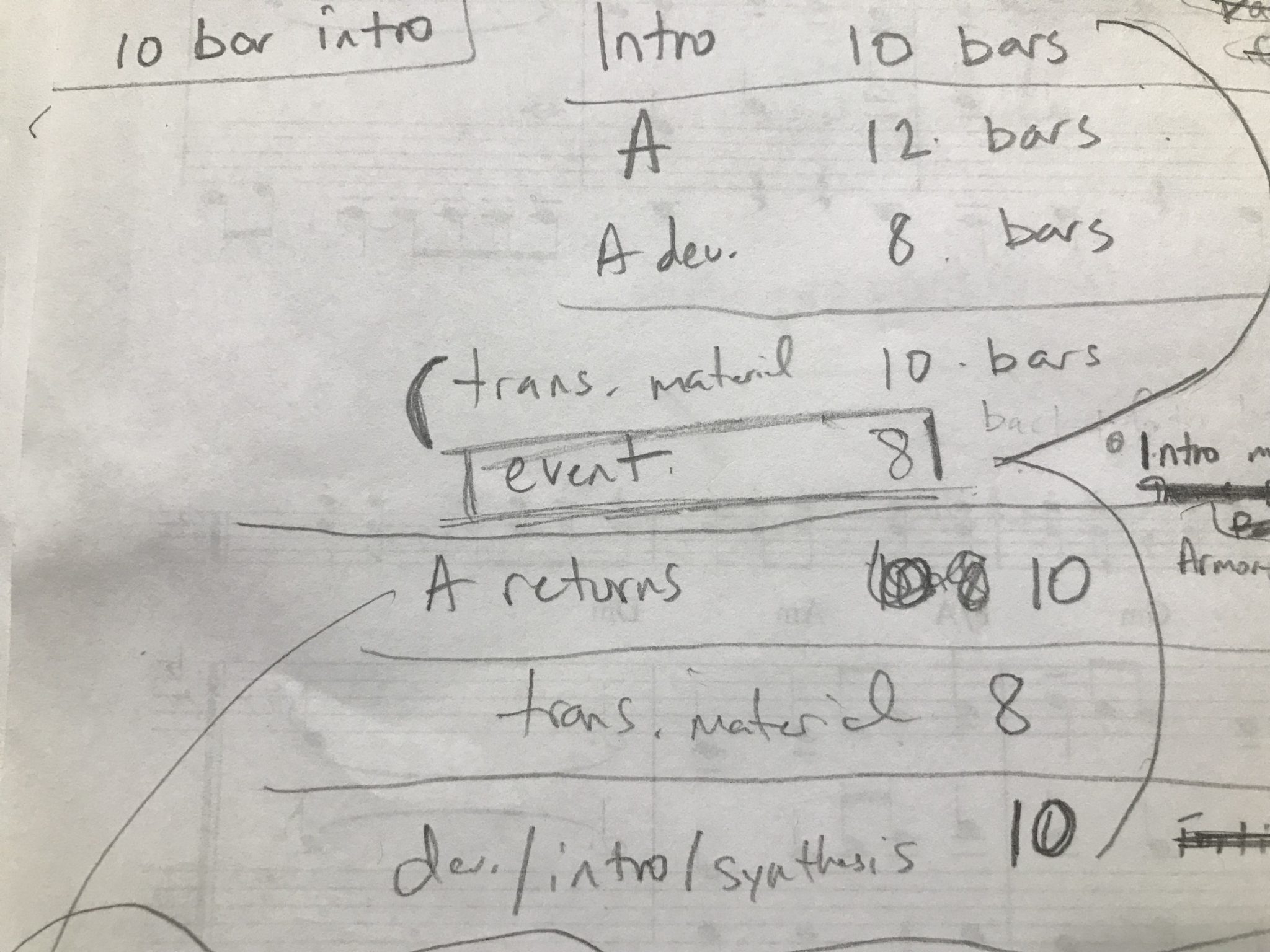

With composition planning, I usually begin after score study armed with inspiration and with my goals in mind, and create a graph, and/or a list of the intended sequence of events, and/or a rough draft of the program notes. Here are some examples:

From there, if I know my intended length, I can get a sense for how much time I’ll have in each section. As an example, if I have a five minute work, I have three hundred seconds. Using the golden mean (for more information about the golden mean, check out this article: https://www.cmuse.org/classical-pieces-with-the-golden-ratio/), I can calculate .618 through the work, by multiplying 300 by .618, which equals one hundred and eighty-five seconds, or three minutes and five seconds. The essence of the golden mean, is that no new information is introduced after that point, so I would then determine how much information I’d like to introduce in roughly three minutes and five seconds. Let’s say I have two musical ideas I’d like to include, in a format something like this:

Introduction

Theme A

Transition

Theme B

To communicate to the audience that the Theme A and Theme B sections are of relative equal importance, I commonly aim to give each section an equal length, in this case possibly a minute to a minute and fifteen seconds each. The remaining time would be divided between the introduction and the transition. Now, if I decided to give Theme A one minute of time, and once I get writing my music I realize the tempo is around 120 BPM and the meter is 4/4 time, I can calculate the amount of space I have to work with in measures. A measure in 4/4 time has 4 beats, which each beat receiving exactly 1/2 second at 120 BPM. Therefore, each measure is two seconds long and since I have a full minute to work with, I divide sixty seconds by two seconds per measure, and end up with thirty measures for my Theme A. For me, it is sometimes easier to think of music in measures than time for composing purposes!

Transitions and Endings

A good transition section typically begins with characteristics like the section preceding it, and transforms into the section immediately following it. Transitions are usually where I personally struggle the most, and is currently the central focus of most of my score study. I often find it most helpful to write the transition after writing the sections before and after it, so that I know where I’m going and where I’ve come from. As of now, I usually employ a methodical approach to transitioning, by using my parameters list and methodically comparing and contrasting the Theme A and Theme B sections (or Theme B and Theme C, etc.) Here is one of my most recent lists for a concert band work:

Theme A

Texture is polyphonic

Tonal harmonic key center is Bb mixolydian

Meter is 4/4, with rhythmic emphasis on beats 1 and 3

Utilizes tambourine and marimba

Dynamic level is loud

Theme B

Texture is contrapuntal, in a conversational style

Tonal harmonic key center is in Eb major

Meter is 4/4 with a rhythmic emphasis on beat 2

Utilizes gong and snare drums without the snares on

Dynamic level is at a mezzo forte

My job at this stage would then be to write a transition that transforms the elements from one to another in a pleasing way. To transition from Eb major to Bb mixolydian, I would at some point in the transition destabilize the Eb major chord. Since the two have the same number of flats, and no accidentals are needed to move from one to another, I might begin to place Eb chords on beat 2. This would accomplish moving the rhythmic emphasis from beat 1 to beat 2 possibly as well, which is another element that needs to be transformed. The transition section should lose some dynamic level to move from forte to mezzo forte, and the marimba and tambourine players would need to taper off, with one player possibly moving to the gong and and the snare player switching the snares off. Finally, the texture would move from polyphonic, which features overlapping musical idea of equal significance, to a contrapuntal conversational texture, in which sections take turns making their statements in opposite descending and ascending directions.

And for our last topic of discussion, endings also have certain characteristics that make a listener realize the story is coming to a close. This is accomplished often times featuring a technique known as synthesis, in which all of the themes presented in the first 60% (or otherwise) of the work come back, sometimes in an overlapping fashion. The typical goal once material begins to return is to finish telling the story by demonstrating how the material relates and contrasts to each other. I wouldn’t want to watch a movie where none of the characters’ stories are finished, or one where I only find out what happens to one of the characters if more than one was introduced and developed. In music, almost always, the main subject, usually Theme A, returns in some form or fashion. And commonly the other main themes do as well. Closing sections are often successful as sounding different on the surface level, but upon further inspection are actually related and derived from earlier material. Almost all listeners will have a strong opinion about whether or not they felt your work ended in a satisfying way from a storytelling standpoint, so make sure to tie up any loose ends!

A common strategy to get started with the composition phase of creating a new work is to write around a minute of music or so each day for a week or two. You might be aware from day to day of how the music might relate, but you might not. At the end of the sketching phase, you should be able to pick one or two themes to use for the work! Sometimes I even bounce these sketches off the performers or commissioner. There’s my thoughts in a nutshell on both listening to and creating artistic music! Now – time to get to work.